Contrary to a common misconception, the North was not without slavery; in fact, most slave traders were from New England, and Brookline was no exception.

“We tend to think if slavery as a southern U.S. problem,” said Barbara Brown, a Brookline resident and member of Hidden Brookline, an organization that aims to shed light on the hidden histories of slavery and freedom in Brookline.

According to Brown, Brookline’s introduction to the slave trade began around 1675 with the enslavement of seven Native Americans. The enslavement of Native Americans was quite common, Brown said, as the government and white people were afraid that young Native American men would rise up against them, as had happened during King Philip’s War.

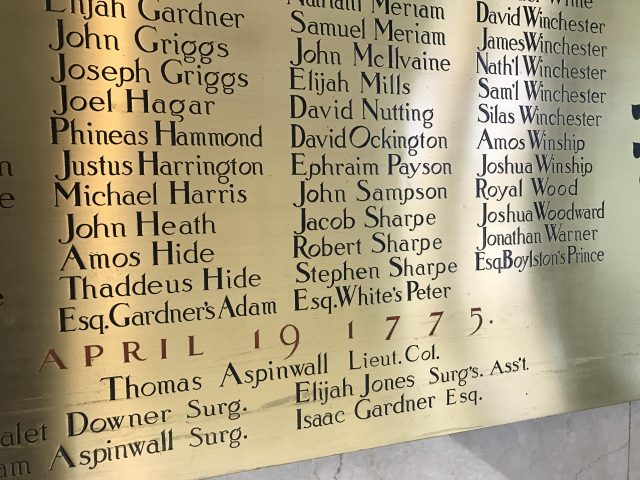

From 1675 to around 1800, the slave trade boomed. Many of Brookline’s household names like Edward Devotion, Henry Sewall, Thomas H. Perkins, Thomas Aspinwall and Joshua Boylston Esq. benefited from the slave trade.

“The slave trade was not considered a terrible thing to do,” said Brown. “It was part of ordinary business practices.”

Though slave traders were common in New England, most slaves were sent to the Caribbean. That is not to say that Brookline was without slaves. During the 1740s, at the height of slavery in Brookline, one household in four was a slave-owning property.

“We have records of people being sold into Brookline, usually around age 11,” said Brown.

Life as a Brookline slave

Life as a slave in Brookline was devastatingly lonely, Brown said. As a farming community, the properties were spread out and slaves were unlikely to meet each other. According to Brown, most slave-owners had jobs that took them away from their property, like military captains, doctors and ministers, so slaves were used to work the land.

“You were not likely to spend time with other enslaved people,” said Brown. “You were on your own and with no one on your side.”

Brown shared one story of a Brookline slave named Sambo, who while serving a meal to his owner and a guest, fell for a trick when his owner asked him which was heavier, a pound of iron or a pound of feathers. Sambo replied that a pound of iron was heavier.

Upon realizing his mistake, according to Brown, Sambo told his owner “well sir, which would you rather have fall on your head from a chimney?”

Though there are few details about Brookline’s enslaved, Sambo’s story is not singular. Going back through records, Barbara has discovered a few enslaved men with similar moments.

“These were men who found a way to maintain their dignity,” said Brown.

Records show that Brookline had a little over 80 enslaved people. Of those enslaved, two-thirds were men.

“The owners did not want women and they did not want children because they were in a place where they could buy new enslaved [men],” said Brown.

The need for inclusion in Brookline’s curriculum

In looking at curriculum in Massachusetts, Brown sees a gap in history lessons where slavery should be.

“We have a hard time in this country, and somewhat in Brookline as making slavery and the slave trade as not one side of our history but as essential to our history,” Brown said.

Slavery needs deeper attention in schools, according to Brown, as it makes up such a large part of history.

“Our notion of what it means to be free comes from this terrible history, our history,” said Brown.

Slavery’s presence in New England clashes with a common perception of the New England colonies as revolutionary and slave free. For Brookline High teacher and Hidden Brookline member Malcolm Cawthorne, Brookline’s history with slavery is not so much surprising as it is typical.

“It’s pretty typical that wealthy people in America were connected to slavery in some way, shape or form,” said Cawthorne.

Having grown up in Brookline and gone to Devotion – named after Edward Devotion, who was a slave owner – Cawthorne said Brookline’s history with slavery was something he was always sort of aware of, and when he began researching it more at an older age, what he learned didn’t produce an ‘ah hah’ moment, rather it made him feel vindicated.

“For me it was always on the peripheral, stuff I hadn’t truly absorbed” said Cawthorne.

This is true for many Brookline students.

Brown recounted a moment that Cawthorne shared with her from when he took one of his African American Studies classes to see the Town Hall plaque that lists the names of men from Brookline who marched to the Battle of Lexington. Included on that plaque are the names of three enslaved men who also marched. Upon learning who those men were one of Cawthorne’s students reportedly said it made him angry, because he had never learned this part of Brookline history.

“I think for a lot of kids, Brookline is depicted as this liberal bastion of fairness and equality, until they find out that’s not true history,” said Cawthorne. “Of course things aren’t fair; the reality of history tells us something different.”

Brookline is taking steps towards incorporating slavery more into the curriculum. About two years ago the schools introduced a unit on slavery into the third grade curriculum. Cawthorne would like to see the schools take it a step further.

Slavery is something that needs to be incorporated in at the high school level, he said.

“We have to give a deeper look,” said Cawthorne.

Remembering Brookline’s 84 enslaved people:

Ackey

Adam

Ben Boston

Boston

Bung

Caesar

Caesar

Charles

Coff

Cuff

Cuff

Cuffe

Dido

Dinah

Dinah

Dinah

Dinah

Dinah

Exeter

Felix

Flora

George

Great David

Hagar

Hawkins

Jack

Jack

Jack

Jackie

Jane

Jenny

Jenny

Jeremy

Jethro

John Indian

Kate

Kate

Kate

Katherine Cuff

Kent

Lemon

Margaret

Moll

Pamela

Peter

Peter

Phillis

Phillis

Pompey

Primus

Primus

Primus

Prince

Quaco

Reube

Rose

Rose

Sambo

Seco

Titus

Tobey

Tounnaquin

Venus

Venus

Violet

Warwick

William

– and eighteen whose owners listed them in documents simply as ‘negro’